This post appears courtesy of Out & About Magazine – view the original post here.

Restaurants, shops, and yes, actual residents, are joining long-time cultural assets like The Grand to begin making Wilmington’s main street vital once again…

Market Street has seen its share of hard times.

The backbone of Wilmington’s commercial and retail life for more than two centuries, the street fell into decline in the late 1960s, ravaged by rioting and a National Guard occupation in the wake of the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968. The continued growth of suburban shopping malls eviscerated its retail core. Market Street’s transformation into a pedestrian mall in the mid-1970s brought a glimmer of hope, but it was short-lived.

Why would a big-name national retailer want to invest millions downtown when the local merchants, who presumably knew better, had decided to close up shop at 5 p.m.—when DuPont employees went home—shuttering their storefronts with forbidding iron gates?

While the passage of the landmark Financial Center Development Act in 1981 would engulf Delaware’s shores with a tidal wave of credit card banks, it meant little to Market Street. The bankers, like almost everyone else in the ‘80s, preferred the suburbs.

In the 1990s, a Market Street turnaround would begin, slowly and quietly, dwarfed by the mega-projects underway less than a mile to the south on the Riverfront—a baseball stadium, outlet shops, restaurants and a meeting center, followed later by office buildings, a movie theater, a children’s museum, townhouses and condos.

With relatively little fanfare, the funky LOMA district between Second and Fourth took shape, with shops and restaurants downstairs, digital marketing and consulting businesses like the Archer Group and Trellist around the corner, and millennials hungry for life in an up-and-coming neighborhood taking over the rehabbed apartments upstairs.

The Delaware College of Art and Design, opened in 1997, would grow steadily to an enrollment of 400-plus students, with many living along Market Street, either in second– or third-floor walkups or in a former hotel recently converted into a residence hall.

In 2011, the venerable Queen Theater would discover a second life (a third, if you count its 19th-century origins as a hotel) in the next two years, joining the Grand Opera House as a destination for city residents and suburbanites in search of top-quality live entertainment.

For much of the past decade, two developers—Preservation Initiatives in the 300 block and the Buccini/Pollin Group from Fourth to Rodney Square—have been rehabbing upstairs residential units and new residents have been eager to move in.

At the same time, Downtown Visions, Wilmington’s affiliate in the national Main Street economic development program, has been supporting local businesses through training programs, marketing, event sponsorship and, most significantly, a façade improvement program financed through loans and grants that has resulted in the removal of most of the storefront security gates. “We’ve done 49 façade projects and 26 of them have included [interior or exterior] building renovations,” says Will Minster, Downtown Visions’ director of business development.

“Market Street’s cultural assets have always been there,” says Mark Fields, The Grand’s executive director, citing his venue, the Christina Cultural Arts Center, the Queen and the just-renamed Playhouse on Rodney Square.

“What we’ve been waiting and hoping for is the rest of what you need for a vital downtown to catch up with us—people living downtown, as much as anything,” he says.

Drumroll, Please

“What we’re excited about,” Fields continues, his voice cracking with enthusiasm, “is we see it coming now.”

And there’s plenty coming … soon.

Figuratively, and in some respects literally, a new Market Street is just around the corner. In early July, if not sooner, restaurateur Bryan Sikora, owner of the popular La Fia Bakery Market and Bistro at 421 N. Market, will have opened two new ventures—Cocina Lolo, a whimsical Latin-Mexican restaurant, on the ground floor of the Renaissance Building, 405 N. King St., and Market Street Bread and Bagel, a breakfast-lunch, bakery and sandwich shop with counter and takeout service, at 823 N. Market.

In July and August, Buccini/Pollin will be renting market-rate apartments at 608 N. Market, just up from DCAD, and across the street at 629 N. Market, once the Kennard’s department store and more recently a Delaware State University satellite operation. By the end of August, BPG will be renting apartments in the three buildings of its Market Street Village: 838 N. Market, the former WSFS Bank headquarters; 839 N. Market, over the Walgreen’s store; and 6 E. Third St. Many of the new residents are expected to be teachers and staff members at three charter schools opening this fall: Delaware Met at 920 French St.; Great Oaks in the Community Education Building, 1200 French St., and Freire, in the former Blue Cross-Blue Shield of Delaware headquarters on West 14th Street. Depending on income levels, residents of Market Street Village may be able to rent a one-bedroom unit for about $800 a month. The 150 units in these projects should add about 200 residents to Market Street.

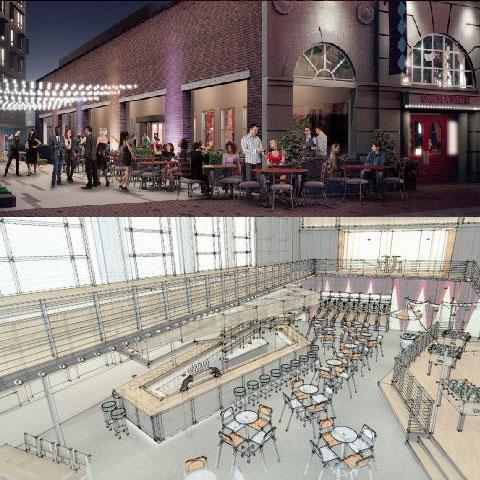

Once these renovations are complete, BPG will ramp up work on the ground floor and lower level of the old WSFS building, transforming the former bank hall (once home to N.C. Wyeth’s famous 1932 mural Apotheosis of the Family) into a recreation hall that will be called Ninth Street Social, according to Sarah Lamb, BPG’s director of design and marketing. Expected to open in the first half of 2016, the center will feature pool and ping pong tables, skeeball games, a lounge area, a coffee/juice bar and enough interior flexibility to host art bazaars, craft shows and social events.

Also in early 2016, Canon Hospitality Management expects to complete the transformation of the seven-story former Beneficial Bank headquarters into a Renaissance Inn at 1300 N. Market. It will be a 96-suite hotel for extended-stay travelers. The building has sat vacant for a decade.

Canon Patel, a managing member of Canon Hospitality Management, the developer of the hotel project, told the News Journal that while this is his company’s first time adapting an existing building, they chose the property because of its location across from the Hercules office building on the northern edge of downtown.

Patel said the location helps with their target audience—business travelers who are staying for more than a night or two.

Next Spring: Chelsea Plaza

By next spring, Scott Morrison and Joe Van Horn, partners in the Chelsea Tavern and Ernest & Scott Taproom, expect to open their third restaurant on Market, which helps explain why the brew pub/barbecue spot at 827 N. Market will be named 3 Doors. The other reason: it’s also three doors up from Chelsea.

Chelsea itself will be getting a new look as Buccini/Pollin tears down 817 N. Market, effectively doubling the width of the pedestrian pathway between Market and Shipley streets, creating an area that will be known as Chelsea Plaza. The remodeled Chelsea will have windows and an entrance opening onto the plaza, where it will have an outdoor seating area. Across the way, 815 N. Market will be repurposed as home to several mini-shops that will also open onto the plaza.

The plaza, Lamb says, will be roomy enough to accommodate small events, things like jazz fairs, craft shows and perhaps a pop-up beer garden.

The greater significance of Chelsea Plaza, Lamb says, is what it will lead into.

Flip the calendar to mid-2017, when BPG expects to open the Residences at Midtown Park, a 200-unit luxury apartment complex on the site of the former Midtown Parking Garage.

Its two buildings, with a 513-space parking garage underneath, will take up most of the northern portion of the block bordered by Shipley, Eighth, Orange and Ninth streets.

Ground floor retail fronting on Ninth Street will serve both residents and downtown workers.

The 300 or so residents at Midtown Park will be able to look through Chelsea Plaza for a dramatic view of The Grand, easily the most iconic of Market Street’s historic structures.

A broad alleyway between the two buildings serves a dual purpose: providing access to the parking garage on one side and forming a shop-lined walkway on the other. This area will be known as Burton Place, honoring the late William H. Burton, an African American former Wilmington city councilman, whose name is attached to a landmark 1961 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that started when he was refused service in the Eagle Coffee Shoppe, which was part of the old parking garage complex, in 1958 because of his race.

Chelsea Plaza and Burton Place would extend, in zigzag fashion, a series of walkways through the middle of downtown’s 800 blocks, from Peter Spencer Plaza on King Street all the way west to Orange Street.

Taken together, the multiple projects and the people moving into the new and renovated apartments could give a nearly-finished look to a revitalization that has been two decades in the making. “When all these things come together in the next 24 months,” Fields says, “it’s going to completely change the dynamics of downtown in a positive way.”

With hundreds of new residents, “Market Street will become more attractive to businesses,” says Patrick Ryan, who moved downtown last year as part of the launch team for the new Great Oaks Charter School. “I expect to see some stores open on Sunday, some to stay open later. I see a place where people will want to hang out and socialize, rather than just going to the Riverfront.”

Projects like Ninth Street Social, in the old WSFS building, are being developed with the critical mass of the millennial generation in mind, Lamb says. “We have plenty of destination entertainment, like The Grand, The Queen and the restaurants,” she says, “but what we’ve been missing up to now has been the local hangouts.”

Forming a Community

Mona Parikh, one of the organizers of Start It Up Delaware, says she has found that the digital and tech entrepreneurs who frequent the coworking space on Market Street are often interested in more than finding collaborators and mentors for their projects. “They’re taking a vested interest in forming a community,” she says.

Like Parikh, Ryan sees millennials on Market as having the potential to become a driving force within a community whose evolution is taking it away from larger businesses and into smaller, more artistic, cultural and tech-driven operations. “Wilmington has a knack for attracting people who are socially conscious, who are interested in giving back to the community —young people who are not scared of the problems, but who are going to embrace the challenges,” he says.

“Ten years ago, nobody lived on Market Street. There are 500 to 600 residents now,” says Mike Hare, BPG’s executive vice president. “No one would have believed that 10 years ago.” He expects Market Street’s steady progress to continue. “The city has good bones. We’re fortunate we have good employers and we have a pretty healthy skyline,” he says. He’s eager to see what happens when the current round of projects is complete. “Every two years there seems to be a new tipping point,” he says. “I don’t think we’ve seen the last one yet.”

Some Cautionary Notes

While the wave of new projects nearing completion and the anticipated arrival of 500 or so new residents has many believing Market Street is reaching the tipping point in a successful revitalization, some with first-hand knowledge of what’s going on are waving a few caution flags.

First, Chemours. After more than a century in downtown Wilmington, the DuPont Co. has moved its headquarters to the suburbs, leaving Chemours, its performance materials spinoff, in what is still known as the DuPont Building. It remains unclear whether Chemours will match DuPont in terms of downtown personnel and payroll (the latter a key issue for a city government that counts on wage tax revenue from well-paid executives). And it’s equally unclear whether Chemours will remain for the long haul or become the target of another corporate takeover.

“It would be a shame to lose a company of that size, but there is definitely a shift happening,” says Sarah Lamb, director of design and marketing for the Buccini/Pollin Group. Noting the growth of tech-based small businesses and entrepreneurial communities like Start It Up Delaware and 1313 Innovation (in the Hercules Building), as well as plans for an arts-tech oriented Creative District west of Market, Lamb says, “All this grassroots stuff kind of offsets changes in the corporate climate.”

Next, crime. Wilmington still has to shake the “Murdertown, U.S.A.” label given it in a December article in Newsweek magazine. Although the incidence of crime in the Market Street corridor is significantly lower than in most other areas of the city, there remains a perception among suburbanites that the entire city is unsafe.

Making streets safe is not only a police duty, it’s a shared responsibility, says Carrie W. Gray, managing director of Wilmington Renaissance Corporation. “It’s about everybody being part of the solution.”

Joe Van Horn, managing partner at the Chelsea Tavern, is a Hockessin resident but he grew up outside Philadelphia and went to high school in Chester, Pa. “The fear issue is zero to me,” he says. “I think this is the safest I’ve ever been in my life.” He points to the irony of how little mention there is of crime when popular entertainers fill The Grand, the Playhouse or The Queen to capacity. “It’s never unsafe on show nights. It’s never a safety issue when there’s someone they want to see,” he says.

Finally, for all the new housing in the pipeline, Will Minster, director of business development for Downtown Visions, questions whether it is enough, and whether it’s directed at all income groups. “We need a balance between affordable, millennials and luxury,” he says.

Buccini/Pollin can’t afford to buy up all the remaining potential residential sites on Market, and merchants who own their buildings, especially in the 700 block, need help through something like the façade improvement program to convert their upstairs space into affordable rental units, Minster says. Minster believes an overlooked target market is made up of the relatively low-paid night-shift workers at downtown restaurants and entertainment venues. Public transportation isn’t a viable option for someone who works until midnight, and parking options are limited for those who must arrive at work before or during the evening rush hour, he adds. “If you’re getting off at 11:30 at night, it would be nice to live down the street,” Minster says. “And it’s their community. They would be more protective of it.”